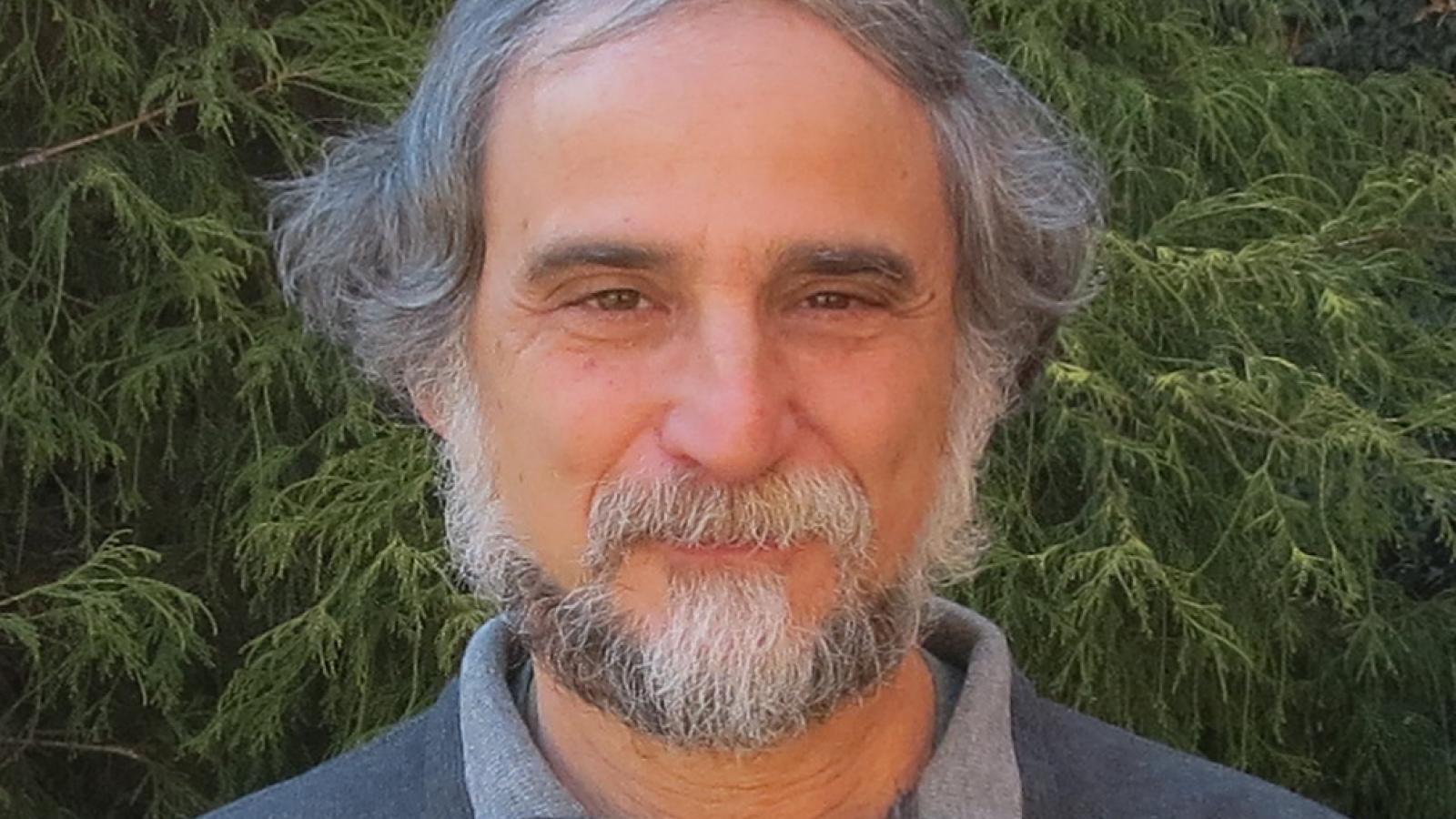

This year, the Ohio State University’s Department of Linguistics marked a major diachronic event: Brian D. Joseph, a member of the department for 45 years, has transitioned from professor to emeritus. While Brian remains a dynamic and productive synchronic force, we take this moment to bear witness to his semicentennial history as a linguist.

It is no accident that, as Brian’s advisee, I often quickly find I have something in common with another academic not long after meeting them: fond familiarity with the work of a certain Brian D. Joseph, if not the man himself. This familiarity, I have discovered, has diffused not only among linguists of diverse concentrations, but also classicists, historians, and beyond. A common theme is that his argument is made imperishible in the memory by a characteristic rhetorical charisma. His logos, persuasive and clear, is accentuated with a certain tad of wittiness.

It is genuinely difficult to exhaustively enumerate the areas in which his voice has echoed. It is even hard to identify any “core” area. It is as if one simply cannot avoid writing on the margins: as Brian has said about language, there is a centrality to the periphery. And if one must pick a thread running through Brian’s work, it is the centralization of the material that had hitherto been left aside as ‘peripheral’. Where others saw naught but the frame of the portrait, Brian saw critical nuances in these margins, and showed how these patterns are meaningful enough to challenge, further develop, and reframe what we make of the picture within.

Brian is perhaps first and foremost an explorer and analyst of the forces at play in diachrony, yet with a keen interest in synchrony. If one has to choose one area of theory he has contributed most to, the (hesitantly) safest answer is probably historical morphology, but it was his work in historical phonology that I was first exposed to, which pivotally shaped my own views, and played no small role in bringing me to OSU as graduate student. At the same time, it is predictable that before long, one encounters a linguist who was first acquainted with Brian’s theoretical contribution to historical semantics, syntax, or sociolinguistics – both regarding contact, and otherwise.

His work has perhaps been most concentrated in Greek, Sanskrit, and Albanian, although the only branch of Indo-European he has not yet contributed to is Tocharian; he has also written on Basque and Cree. Brian has also deployed his sharp eye for detail in language-specific analyses in the service and refinement of global linguistic theory. Among many other topics, this is particularly visible with respect to debates on grammaticalization and (de)morphologization, in which Brian has gone against the grain and, convincingly for many, argued for greater nuance. Brian has also gained traction in his arguments that we should morphologize our understanding of various elements hitherto considered lexical, Modern Greek pronominal affixes and other elements of the verbal complex, and, with his former student Andrea Sims, the parallel verbal complexes of Albanian, Balkan Romance, and Balkan Slavic as well. One must also mention the Big Bang Theory of Sound Change, and Brian’s compelling reanalysis of cases of apparent drift as sociolinguistic `bubbling up’ of hitherto submerged variation, now termed supervescence. Although more known for his contributions to the ‘armchair linguistics’ of analysis and theory, Brian has also undertaken various fieldwork endeavors, in Greece, Southern Italy, Albania, and Lithuania.

Brian’s name is also quite visible in his role in writing and editing various books and journals covering broad (but especially historical) linguistic theory or Indo-European. His seven authored books and twenty-one edited books and collections include five reference works on broad historical linguistics theory, including the particularly popular The handbook of historical linguistics (two volumes, with Richard Janda), and Language history, language change, and language relationship (with Hans Heinrich Hock), and the book series Empirical Approaches to Linguistic Theory. In phylogeny, he also co-edited the popular Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics and Nostratic: Sifting the Evidence. He has served on the editorial boards of, among others, Brill’s Studies in Historical Linguistics, the Journal of Historical Sociolinguistics, and Word, and has served as editor-in-chief of Diachronica, Syntax and Semantics, and Language.

One frequently sees Brian bringing new data and analyses to broader matters, and while he draws from many languages, he has drawn from and contributed to Greek linguistics particularly early and often, focusing especially on synchrony, diachrony, dialectology, and relating these different angles. Brian’s second and third published works, written before he turned 24, concerned Indo-European laryngeals and UG understandings of verb raising respectively in Greek. His dissertation, now published, was Morphology and Universals in Syntactic Change: Evidence from Medieval and Modern Greek; he also co-authored Modern Greek with Irene Philippaki-Warburton, and edited five other books and collections on Greek linguistics, often with an eye to broader theoretical relevance. He is the founder of the Laboratory for the Study of the Greek Language, and has served been editor-in-chief of the Journal of Greek Linguistics since its foundation in 2000, during which he has also served on the board of Symposium, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, and Albano-Hellenica.

Panos Pappas, Brian’s former student, collaborator, and now a professor at Simon Fraser University, remarked that “Brian is a key figure in Greek linguistics whose work introduced important theoretical innovations to the study of the language… [and] elevating Modern Greek within the field… he has been at the vanguard of a new era of research in Greek Linguistics and inspired dozens of scholars to follow in his footsteps leading to exponential growth in the field.” For his contributions, especially in Greek diachrony, synchrony, and dialectology, Brian has been awarded honorary doctorates by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Patras, as well as an honorary professorship at the latter. In addition to bringing Greek facts to the center of theoretical and Indo-European debates, Brian also brought attention to hitherto marginalized aspects of Greek, such as the ‘marginal’ phoneme /t͡s/, the dialects of Tsakonia, Lesvos, Adrianople, and Palasa, and the membership of Greek in the Balkan sprachbund.

Brian’s role in OSU’s Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures as the Kenneth E. Naylor Professor allowed him to further his work as a Balkanist. Brian the Balkanist initially grew out of Brian the Hellenist, but his work on the Balkan sprachbund soon stood tall on its own. In the preface to the 2019 festschrift And Thus You Are Everywhere Honoredː Studies Dedicated to Brian D. Joseph, the preeminent Balkanist Victor Friedman noted how, soon, after first encountering Brian in 1980, he read the manuscript of his The Synchrony and Diachrony of the Balkan Infinitive, which he recognized as a “qualitative shift” from the established model of Balkan linguistics in how it related synchrony and diachrony; Victor became a long time friend and collaborator with Brian. Brian’s work on the sprachbund, both on its own terms and as it informs areal linguistics as a whole, will soon include his greatly anticipated collaboration with Victor, The Balkan Languages, to appear in March 2025. This is no small oeuvre, but over 1200 pages of meticulous work spanning 20 years. Here again, Brian’s knack for making us appreciate the relevance of supposedly `marginal’ elements shines through in meticulous consideration of nonstandard dialects, inclusion of Balkan Romani and Judezmo varieties, and appraisal of various oft-ignored elements such as “ERIC loans”, which signal enduring and intimate contacts. Brian’s work in Balkan linguistics has made him a figure of some public interest, with popular newspapers such as the Greek To Vima and Albanian Koha having ran interviews of him, as did national TV programs in Greece, Albania, Kosovo, and North Macedonia.

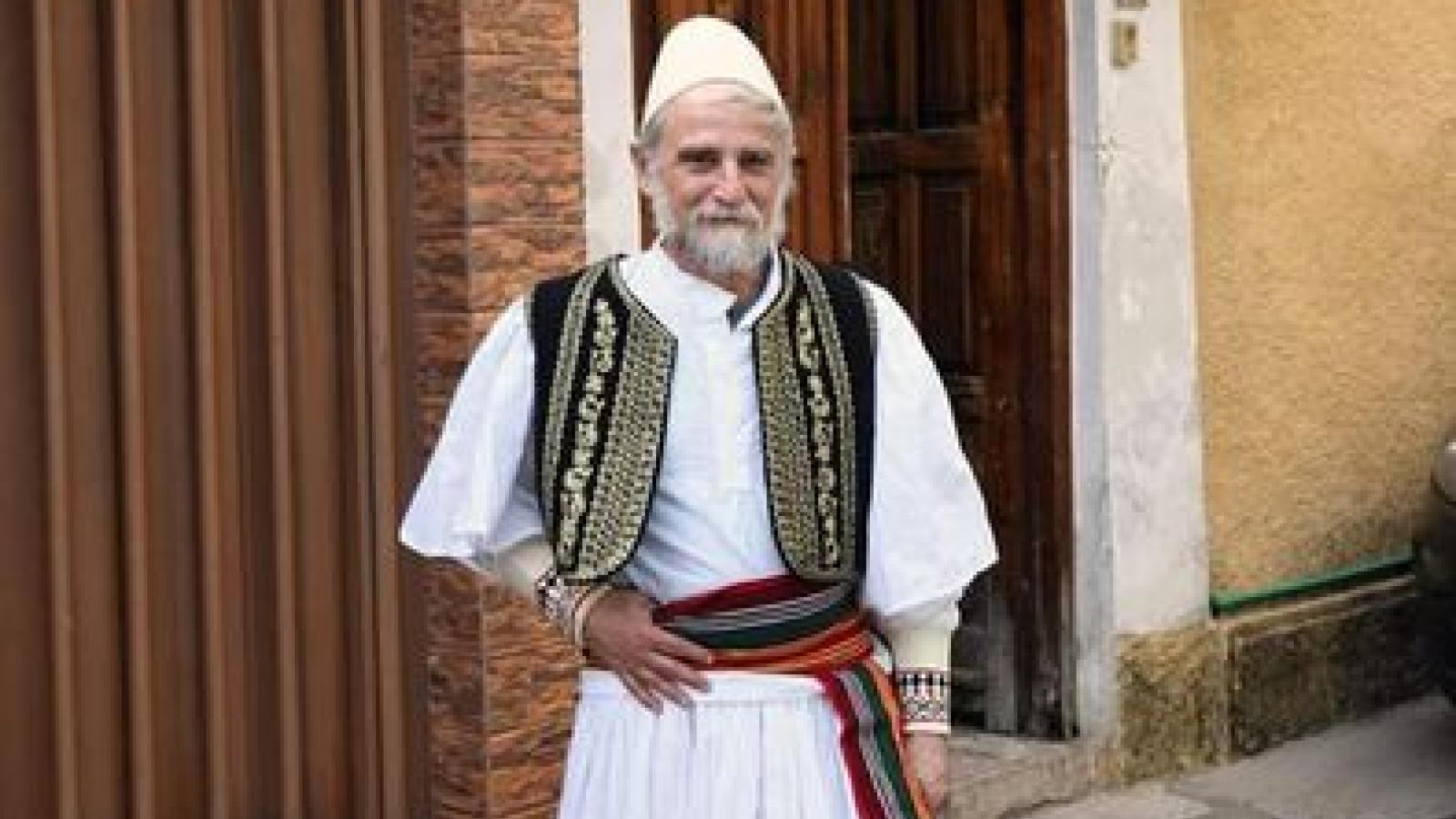

Brian the Albanologist grew out of Brian the Balkanist and Brian the Indo-Europeanist; Brian has remarked that it was after he became the Slavic department’s Naylor professor that his “interest in Greek in its Balkan context” crystallized in such a way that it led him to Albanian. His work on Albanian tends to position the language in its areal and phylogenetic context, and bring the Albanian angle to questions in Balkan and Indo-European studies, building upon the legacy of Eric Hamp. He has especially focused on Albanian historical syntax and lexical semantics, as well as its historical relationship with Greek, which he has proposed it forms a clade with in Indo-European. Brian’s contributions here have been recognized with honorary membership in the Albanian Academy of Sciences (ASH) and the Kosovo Academy of Sciences and Arts (AShAK).

In fact, these honors in Albania and Greece stand among a much larger body of academic honors, both those bestowed by OSU, and from elsewhere in America, Europe, and Australia. Listing these would be downright tedious, but it is a reflection of the depth and breadth of Brian’s service to the field, not just in research, but in outreach, in mentorship of graduate and undergraduate, hosting visiting scholars and conferences, in editorial and reviewing work, and last but certainly not least, serving as president of the Linguistic Society of America.

But in all of this service, it is his role in our department that we reflect on, in the context of his retirement. Brian joined the Ohio State University’s Department of Linguistics 45 years ago, making him the department’s longest serving professor. At the time he joined, the department was fairly small, and while it included “big names” as founding or early members, many of these were drawn away (quite often to UC Berkeley, curiously). By the final decade of Brian’s tenure, OSU linguistics has come to consistently rank in the top 20 linguistics departments worldwide. Brian played a significant role in this evolution, in his research, advising, teaching, and especially his ten years as department chair. These years, 1987 to 1997, were a period of expansion, with the recruitment of nine faculty members, including major names in contact linguistics, phonetics, syntax, and computational linguistics. This expansion in personnel consolidated OSU’s status as a research powerhouse in the late 20th century. This broadening of topical coverage and advisor availability also greatly increased the appeal of OSU linguistics to prospective students, as did the fact that the department, under Brian’s watch, hosted the 1993 LSA Summer Institute.

The reputation of OSU linguistics has also been bolstered by its alumni and their accomplishments, many of whom directly credit for Brian for fostering their development. Brian has guided 46 graduate students to completion of PhDs which he has overseen, all covering topics in linguistics; most of these were in the linguistics department, while a few were in Classics or Slavic, but with ties to our department. He continues to advise his remaining four linguistics doctoral students in his retirement. His first graduate student, Rex Wallace, graduated in 1984 and retired well before Brian did, but returned to OSU to take Brian’s class on Hittite with Brian’s then-current advisees (including myself) in 2022. Just as Brian’s “first (language) love” was Latin, his first PhD student went on to become a preeminent scholar in Latin, other Italic languages, and Etruscan, including nine collaborations with Brian. Reflecting on Brian’s role in his own evolution, Rex had the following to say:

In my estimation, Brian was not only an amazing scholar and teacher, but a superior mentor to graduate students in the OSU linguistics program. He ensured that those of us working in the fields of historical linguistics and Indo-European studies were up to date on the latest developments, and stressed the importance of the history of the field and the contribution of its most illustrious scholars. When it came to my own research and research papers, Brian provided an ideal model to emulate in terms of the quality of the research, the analysis of the linguistic data, and the presentation and structure of the argumentation. He vetted the scholarly papers I wrote under his guidance as a graduate student with the utmost rigor… More important, he also introduced me to the national linguistic conferences in my field, to the cogent writing of abstracts, and to the preparation and delivery of papers. His keen insight into the business side of the profession, in particular how to interview for scholarships and jobs, helped me secure the Rome Prize Fellowship at the end of my final year as a graduate student. I carried his pedagogical and scholarly guidance with me for the entirety of my academic career. Big thanks, Brian!

Panos Pappas, who completed his PhD under Brian’s wing in 2001, likewise remarked that “a big part of [Brian’s] success in inspiring a new generation of scholars is due to his dedication to his students and his superb abilities as an advisor… he has served as a role model, someone that I strive to emulate both in my research ambitions and in how I treat my students and colleagues.” Julia Papke, who graduated in 2010, attributed how much she got out of her time studying with Brian to him being both “an intellectual powerhouse and… having such patience and kindness for his students”; Shuan Karim (2021) remarked that Brian was “like a father” to him. His student Andrea Sims, who has since established herself as major voice in theoretical morphology, remarked that she felt “so fortunate to have Brian as my graduate advisor, mentor, colleague, and friend. Among the many, many things I have learned from Brian, one was to have respect for real data, the language as it is used, in all of its idiosyncrasy. I count myself lucky to be one of his academia nuts.” Micha Elsner, a fellow professor at OSU, noted that he had always been impressed by Brian’s generosity in collaboration and mentorship for graduate and undergraduate students alike; his collaborations with former students often continued long after their graduation. For some, like the aforementioned Rex, Panos, and Andrea, this manifests as a paper trail, while it looks different in other cases. For example, on his CV one counts no less than 27 collaborations with his former student Hope Dawson after her graduation, including conferences hosted, a textbook, and presentations, especially on Indo-European topics, pedagogy, and the history of the field.

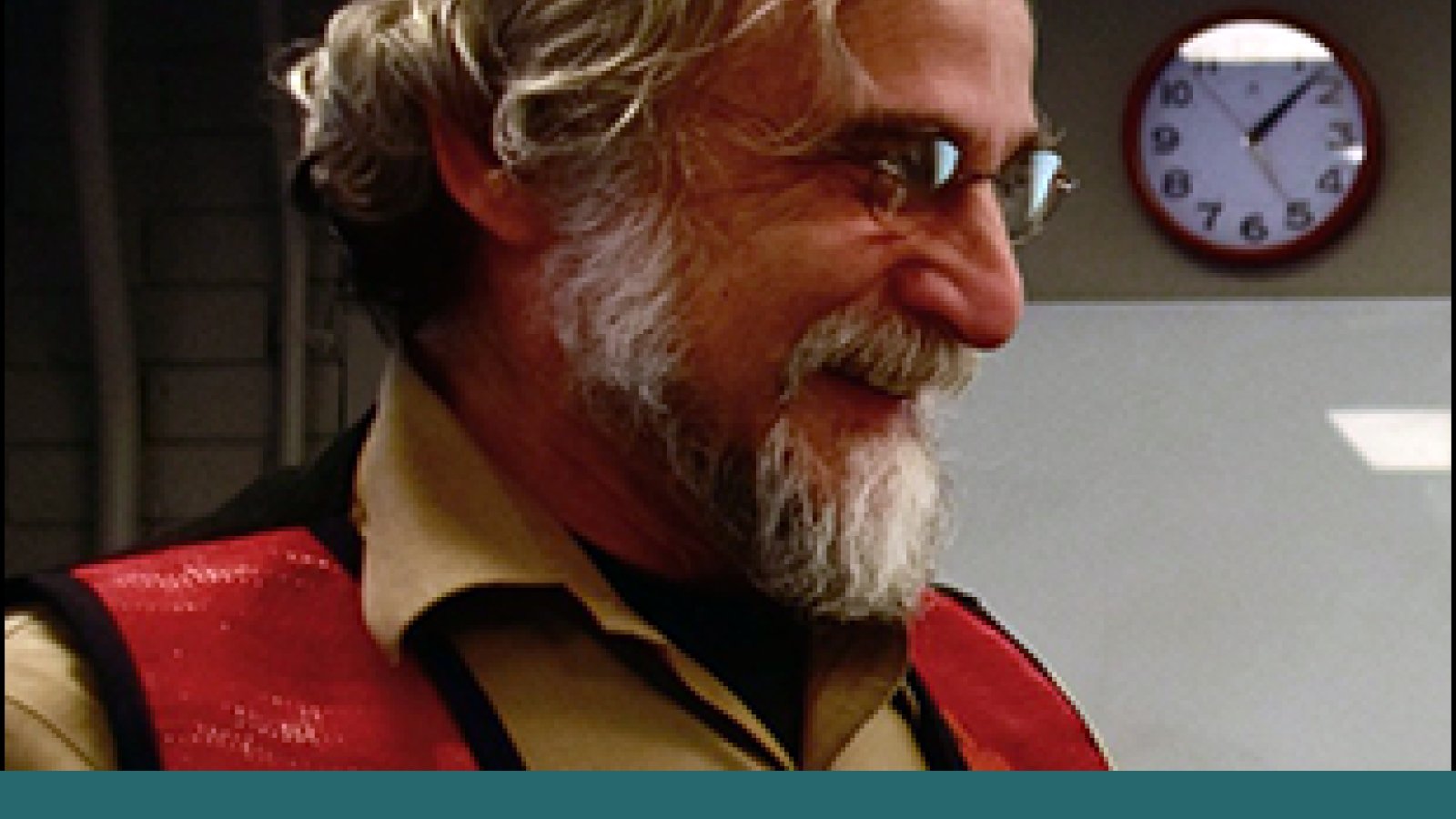

Brian is also notable for cultivating a number of external collaborations. Of those not already mentioned above, particularly notable is his partnership with Richard Janda, which has thus far produced 17 works, spanning from 1986 to 2023. These notably include their Big Bang Theory of Sound Change, which drew data from various corners to present a new take on how phonetically-motivated regular sound change can reshape in its life trajectory, which proved to be influential in historical phonology and, I must add, formative in my own development. Other particularly notable fruits include their jointly edited Handbook of Historical Linguistics, the concept of a diachronic constellation demonstrated in Sanskrit and Greek, and, in classic Brianesque centralization of the periphery, an appraisal of systematic hyperforeignisms as evidence of rule generalization.

All in all, Brian’s retirement is the end of an era for the department, but it is not a conclusion to his legacy, but rather a milestone within it. His legacy continues, and will continue, to grow, as his words echo in the field of linguistics. The field of linguistics may wonder when this process will no longer be productive, but the appropriate question is not when but if. And in the appropriate answer, the uncertainty lies in the phonetic form, not the semantic content conveyed:

... that is, in Proto-Indo-European: “not ever; not on your (long) life”.

-- Clayton Marr