Ohio State’s linguistics department has always been known for fascinating and sometimes creative “rare” course offerings long beloved by students, such as Ling 3801 “Codes and Codebreaking”, with its nerf guns, and LING 3502 “Klingon, Elvish, Dothraki: The Linguistics of Constructed Languages”. But while these two examples are both undergraduate classes that are frequently offered, this semester notably featured much “rarer” classes at higher levels, which are not frequently offered at Ohio State or elsewhere.

LING 8300 this semester was Sound Change and Sound Structure, a class taught by Becca Morley and focused on the interaction between models of phonology and models of phonological change. The students, who were PhD grad students working on phonetics, phonology and historical linguistics, were introduced to a wide variety of models relevant to ongoing research. This included exemplar models, articulatory phonology, listener-based models, and language-parametrized stable state models, among others. One student remarked that the class had really made computational models accessible to him. Another remarked that the class had really brought to light many of the important phono-cognitive models that he had only vaguely been aware of before, and really gave a much clearer picture of the players in the current theoretical debates, especially on the question of the actuation of sound change.

If you have spent the last few months watching in suspended disbelief at the rapid advances of AI of late, you would certainly not be alone. The flow of news about systems such as ChatGPT and Generative AI made the offering for LING 8800, Controllability and Explainability in Neural Language Generation feel even more relevant. As doctoral student Christian Clark remarked, it was “a very timely opportunity to dig into models like ChatGPT that have kindled so much public interest”, while “getting to know how they worked on a technical level” while discussing “broader social concerns” such as “encouraging models to produce prosocial dialogue.”

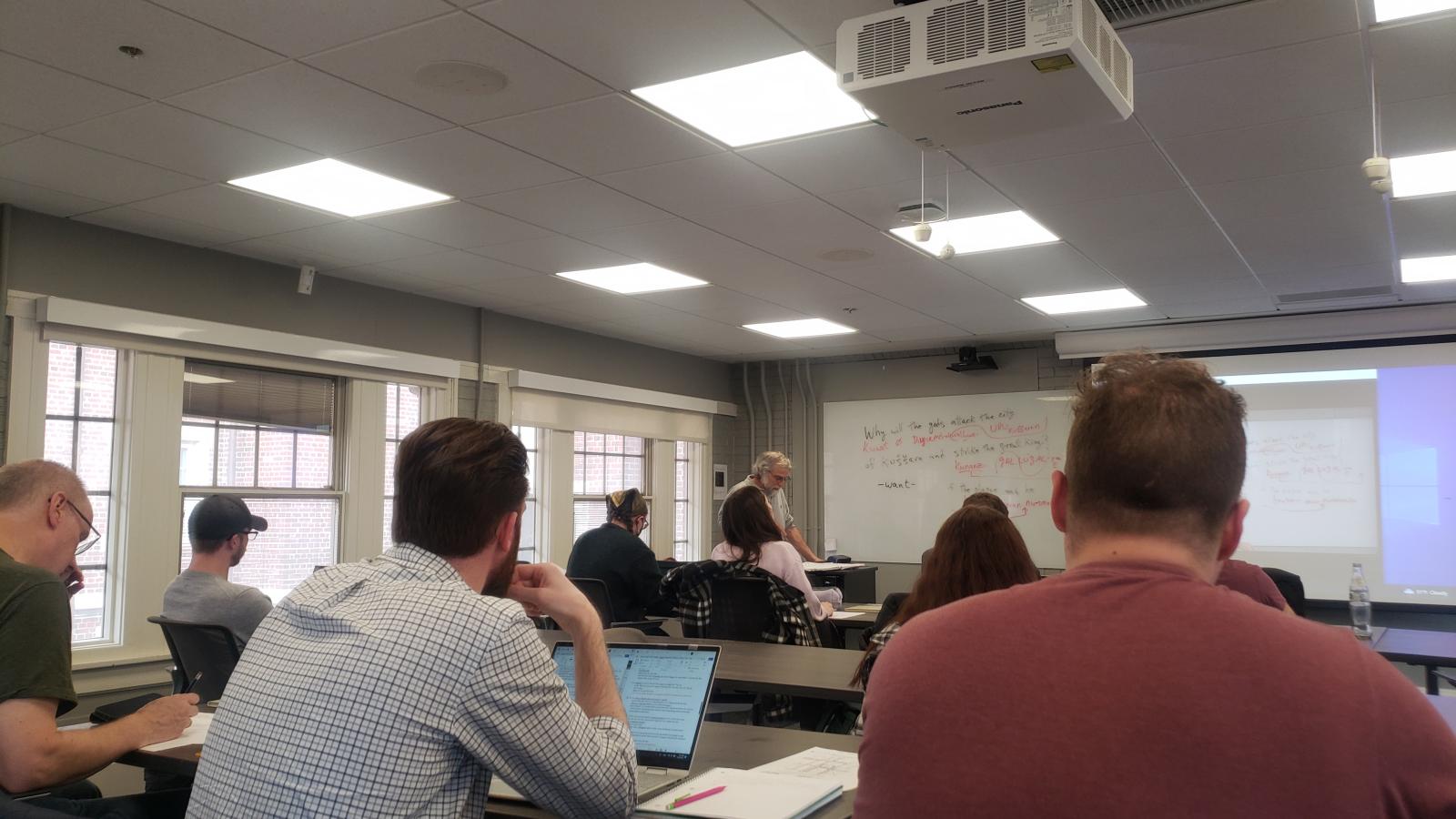

Hittite was taught this semester as LING 5906, taught by Professor Brian Joseph, and drew heavy enrollment from not only undergraduates and graduates alike, but also a number of professors, including some from other departments. It also drew in alumni, such as Shuan Karim, a graduate of our doctoral program who will soon take a postdoctoral position at Cambridge. When asked why he took the class, he said “Hittite? Of course, sign me up! Anyone who misses this opportunity is an idiot.”

While surely there are many highly intelligent people in the world who would not see taking Hittite as the right decision for themselves, it is notable that courses teaching Hittite are quite rare, and most linguistics programs do not ever offer them. Rex Wallace, a quite significant Italicist at UMass, now retired, recalled how much of an event it had been when he had had the opportunity to take Hittite once in the past: it was an occasion that the participants made a shirt to remember.

However, Professor Brian Joseph himself had quite a bit more experience with Hittite classes and Hittitologists. He took three Hittite classes as a student: one semester with Jay Jasanoff, as well as two semesters of Hittite instruction from his advisor Calvert Watkins while a graduate student at UCLA. His classmate Craig Melchert, a fellow graduate student at the time, would later would go on to be a leader in the field of Hitttitology and Anatolic languages, referred to waggishly by his peers as “the world’s first fluent Hittite speaker”; as such, Craig Melchert was also a source of Brian Joseph’s education in Hittite, having given colloquia on the topic as well. Brian Joseph also has taught Hittite a few times before; in fact, he remarked, each past time he had taught it, the experience led to a new paper as he came across new things in the process as he revisited his past notes on Hittite.

The class this spring focused not only on learning Hittite grammar and practicing translations of inscriptions, but also on the place of Hittite within Indo-European as the oldest member of the Anatolic branch. Having branched off earlier than any other part of the family, the Anatolian angle allows a particularly useful vantage point from which one can perceive roots of the family tree that are only hinted at in the other branches. This is most famously the case with how Hittite directly attests reflexes of two of the so-called “laryngeals” of Proto-Indo-European, which elsewhere almost totally vanished, detectable only through the traces of their influences on nearby sounds. But insights from the perspective offered by Hittite are by no means limited to things like this. As Ian Cameron, a Germanicist and doctoral student within the department remarked, Hittite had also given him new insights on the origins of certain morphological classes in Germanic. Class discussion on topics of interest to Indo-European broadly was always lively, as the class brought together an array of specialists in Slavic, Italic, Indic, Iranian, Albanian, and Germanic. The class will be remembered fondly in the years to come.

Only time and the registrar will tell what things may be offered next spring, though there are already rumors that an Old Irish class is in the works.